Learn about the seasonal cycles of the farm, meet the flowers and the farmers.

A Home-grown Retreat: Ringing in the new year with silence

On the first day of 2022 the sun rose into a cloudless sky, emerging from star-studded darkness and quiet. With my partner, Mike, I rang in the new year silently, savoring the last hours of a self-directed ten-day meditation retreat at our farm homestead. Outside, the garden chimes jingled in the cold morning wind. The quiet was ringing inside my body, an outgrowth of this time we set aside to meditate.

There is no way we would attempt to do a home meditation retreat without first experiencing a formal one. Two years ago, we began the new year at a Vipassana retreat center in Joshua Tree, just as we were closing on our dream farm. This retreat was extremely challenging—both mentally and physically. Sitting for ten hours a day summoned pains from old injuries and places I held stress in my body. They amplified with my attention and a host of negative reactions from fear and doubt to anger and frustration arose. The mind state in which I arrived was akin to a bucking, unbroken horse saddled with untamed thoughts. Chief among them was planning and excitement about this new farm and homestead we were in the process of buying.

I asked the teacher during an interview for advice about how to manage the thoughts. She looked at me with clear eyes and said, “Your mind is like a T.V. —it’s a distraction. Any time spent here giving those thoughts your attention will be wasted. When this is over, you will be so clear. Keep working.”

My mind, my thoughts were exactly like a T.V.! It felt like being in a restaurant with someone you really want to talk to, yet your attention keeps getting pulled away to the screen behind them. As a result, you are less present with the person and the conversation. Yet, you gained nothing from the T.V.!

The home meditation altar in the early morning winter light

At the Vipassana center, they removed most of the distractions—namely cell phones; yet even scented products were prohibited. Men and women were separated at all times. The rooms were unadorned and even books and journals were not allowed. There were agreed upon rules and a set schedule. Only my mind remained (and of course the plants growing along the center walking paths) as distractions from the instructions, which were sitting and following the breath and sensation in the body. As I stayed present with the breath, I noticed how these elements arise and pass, and how this is the inherent state of change at play in the universe. I clicked off the thought channels, “smilingly” as our teacher instructed, each time the mind wandered away. By day 8, they came less frequently and a sense of calm entered my body. On a walk in between sittings, it dawned on me that I did not have to do it all! I could leave my job, and make a livelihood from my new farm. I left the retreat center with my mind clearer than ever.

When I entered the stream of daily life beyond the retreat center it was difficult to maintain that hard-won clarity and attention to mindfulness. Quickly the old habits returned. The home retreat came with its own set of challenges that are are presented in daily life. Remembering the clarity I felt after our first retreat, I was motivated to get clear and concentrated so I could focus my energy to realizing the vision for our farm and my business. How can these flowers and gardens serve the highest purpose for cultivating beauty, joy and well-being?

We did our best to remove distractions, create a firm schedule, and simplify our meals. Irregardless, the home environment is full of distracting objects and the farm was full of unfinished tasks that loomed in front of me. Many areas are still being developed, so during walking meditation instead of focusing on placing my feet, I was designing a perennial garden. Fortunately, stormy, cold winter weather conspired in our favor, which made it easier to focus inward, and let go of the gardens and plants. They too, are resting in dormancy.

For me, the home environment (and my workplace) was the perfect place to notice distractions when they arise. I resisted the urge to adjust a crooked painting on the wall. I noticed how books I’ve had for years suddenly called out for me to read them. I resisted the snack shelf over and over. The practice of letting go of objects, whether they be thoughts or things, is so freeing! As the days wore on, I noticed how mindfulness extended beyond walking and sitting meditations. Each activity was infused with mindful attention—standing up, sitting down, putting on clothes, and even washing the dishes! I noticed the joy of savoring the glow of candlelight in the morning darkness and the pleasant sensations in my body as I stretched into wakefulness with yoga. I savored the first cup of coffee; the warmth of the cup in my hands and the potent aroma from the first sip to the last, while I slowly chewed my toast.

It was interesting to notice the contrast in the quality of my attention on everyday tasks. I realized that most mornings I gulp the last sips of coffee and shove toast in my mouth as I stand in the kitchen before rushing outside to do something deemed important. I become frustrated when I can’t get my clothes on fast enough and untangling the twine that supports plants erupts into a frenzy of hurried frustration while I swear under my breath at the plants, twine and even myself!

It is powerful to continue the mediation practice and see how the mindful awareness shapes our environment and our interactions of daily life. What are the simple things that bring about joy, well-being and creativity? How can we cultivate those aspects of life? As we emerge into the rushing, distracting world, I hope to maintain the practice of loving, mindful attention and watch how this grows on our farm and beyond.

What the Trees Teach: Living amongst the giants

As we enter the darker side of year, the veil between earth and spirit realm is a gossamer curtain. As the leaves fall and the days grow shorter, I sense the transience of each moment. It is time to say goodbye to the garden and I grieve the loss of all of my flowers. A few marigolds are still blooming, and I leave them for the bees and butterflies who may be visiting ancestors from other realms.

Many details about my ancestors and those who lived on this land are not known. Both my maternal and paternal grandmothers, descended from Ireland and Scotland, died before I could be imprinted with their foods and gardens, their smells, or the sound of their voices. On this farm I found pottery shards dating more than 1000 years old. There is brick storage box with protective metal door nestled in the limestone cliff and a 100 year old remnant pear tree still stands watch and yields delicious fruit. On Samhain or Day of the Dead celebration, I called in my ancestors and those who tended this land. I built an altar and placed photographs of my grandmothers and lit candles to let them know I am thinking of them.

This year I am mourning the loss of one of our giant Arizona ash trees—nearly a century old—which felt like losing a relative. Once some time back, the main trunk was topped, and rot crept into the heartwood, extending throughout its core to the roots. The tree leaned over the high tunnel growing area, composting toilet and two outbuildings. An arborist deemed it a “hazard tree,” and I struggled for several months with the decision to remove it. It took a crew of arborists and tree workers an entire day, several chainsaws and a crane to safely take it down. Not to mention a big chunk of my savings.

Arborist removing one of our beloved Arizona ash trees

Now, when scanning the farm horizon, my eye rests on this exposed spot, like a missing tooth. However, this tree’s spirit lives on. The rotted slab is the foundation of the altar, another solid section was milled and is curing for a future table. The canopy is a heaping pile of wood chips for shading garden paths. There is a steady supply of firewood and a circle of giant stumps for gathering around the fire.

At 3500 feet elevation in the desert, it is extraordinary to live beneath this extensive canopy of shade. Farming in the carbon-rich understory, my plants are protected by the underground communion between roots, microbes and fungi. The soil sings with the rich organic matter and diversity of living beings transporting water, nutrients and signals through these root systems.

Arizona ash (Fraxinus velutina) are native to the American southwest often growing near a permanent underground water supply. Guidebooks record them extending to heights of 40 feet and living for 50 years. Yet the trees on the farm have a stronger presence at nearly a century old. They form a protective, magical grove along a limestone cliff reaching nearly 100 feet tall, arching into the desert just beyond the boundary of the farm.

In my daily work is easy to be swept into the micro tasks—a dozen flower crowns for an upcoming wedding, the cool season flower seeds and bulbs that need to be planted, and gardens ready to be tucked into bed for the season. The imposing yet benevolent statues of these trees literally shake me back into the present moment, garnering my attention with the delicate sound of leaves raining down with the slightest gust of wind.

Towering Arizona ash trees are pillars of the farmscape

This fall, we spent several Sunday afternoons lying beneath the blazing yellow-orange leaf canopy, which seemed to be shimmering with light inside and out. What was once a mass of dense green shade was drained of life. I marveled at the effortlessness with which the trees released the energy of everything they had grown this season. Leaves sailed down from the tops of the ash canopy with giddy abandon against an impossibly blue sky. Each leaf met its inevitable moment with the ground as if dancing to silent music. Some flew off as if on a mission, others meandered down, as if skipping through the sky. A few tumbled clumsily and others spun and twirled like pinwheels. I too, became giddy with the freedom and levity of being covered in leaves. I felt wealthy surrounded by all this gold laying on the ground. I remembered a line from the Mary Oliver poem, Song for Autumn:

“In the deep fall

don’t you imagine the leaves think how

comfortable it will be to touch

the earth instead of the

nothingness of air and the endless

freshets of wind?”

Growing up in rural Vermont the forests were dark with tree canopies. From an early age I sought refuge amongst them. Even then I was communing with my ancestors; unconsciously, allowing myself to be guided by the ways of plants and trees and forests. I wandered the thick, mossy groves of Mount Flamstead behind our family home experiencing the subtle seasonal changes and a now familiar ache in my heart at the sight of flaming autumn leaves against blue sky. I loved climbing them and dreamed of building my own treehouse for a solitary, watchful escape. The trees on the farm bring me back to my little tomboy self and to the wonder I experienced. I remember how the trees comforted me as a child. The woods soothed and guided me, they awakened my heart to beauty and my mind to curiosity. I felt that the earth loved me wholeheartedly.

The author as a child communing with trees

With the trees on the farm I feel the same tenderness, as if I am sheltered, held, and protected in the earth's wisdom and embrace. My ancestors and those who lived on this land were intimate with the earth’s cycles and when I am quiet they whisper to me through the trees. We are not separate. We are nature.

We are the Seeds: Tethered to the fate of plants

Milkweed plants exploding with seeds

Seeds are tiny miracles. I never tire of witnessing them burst from the soil—full of purpose. Our monsoon pumpkin patch grew fast and furious in the long, rainy and humid summer days. When I survey the tangle of vines bearing pumpkins—some over 20 feet long— it seems impossible that they were once tucked inside a teardrop-shaped seed smaller than a dime. They grow infinitely, tendrils grabbing onto anything they can find to get closer to the sun. I am stumped by a mystery pumpkin that does not resemble any of the seed packets in my collection. A single plant made a dozen giant pumpkins, each one its own work of art, in subtle shades of beige and blush, like the glow of the fading autumn sunset.

Digging through my seed cache, I found a brown packet folded into a triangle with a hand drawn pumpkin labeled dessert pumpkin. I remembered getting this gift several years ago at a seed swap. We crowded inside a farm yurt where a friend was living in exchange for work trade. The winter squash outnumbered the women—giant Hopi curshaws curing on the shelves amidst my friend’s winter sweaters and pantry supplies. Perhaps this could be the origin of the mystery pumpkin?

Wild Heart Farm pumpkin patch harvest (mystery pumpkins are the large Cinderella type)

Pollination requires timing and precision almost as if someone is calling out stage directions: Places everyone! Stigma receptive? Ready for pollen? Anthers loaded? On a single plant, pumpkins have individual flowers that produce pollen and others that have an ovary and produce eggs that must be fertilized to make seeds. This is why we need the bees or Q-tips. The flowers are only open for one day and if they are not fertilized they shrivel and do not make a pumpkin.

As a farmer, I have experimented with seed saving and had some wins and losses. In the process, I marvel at the specificity of each flower anatomy and reproductive strategy. I honor the trials that generations of growers employed and carried forward to build the foundation of knowledge where I now dwell. You can appreciate this in the colorful pages of seed catalogs; the years of breeding to select for qualities like double blooms, taste, and resistance to disease.

Seed saving also requires precision and patience. If you want the varieties to remain true, you have to isolate the plants and insure they cross pollinate with another variety. This is why the squash that sprout from the compost pile resemble distant cousins of last year’s and may not taste the same, as they were “promiscuous,” and now carry traits from other squash growing nearby.

Mystery pumpkin ripens high in the pear tree safe from javelinas

Seed savers keep the stories and traditions alive, and some heirloom varieties can be traced back to a region, family or timeframe. I was touched when Ruben, who helped me build a fence to protect the garden from javelina, gave me squash seeds from his village in Chiapas, Mexico to grow. He has been in the U.S. for 10 years and has never been able to return to his homeland. The seeds hold the memory and food traditions of home. When we save seeds in our garden they preserve the potency of place in their DNA.

For me, saving seeds is an act of rebellion, of resistance and resilience. Many seeds on the market today are F1 hybrids; the result of selective breeding from different parent plants in order to create offspring with those characteristics. They have a place in my garden because of their productivity, desired characteristics, and reliability to variety. However, F1 hybrids are either sterile or the seed will not breed true. We must buy the seed again the next year, and the company that bred them owns the patent on that seed and the profit.

Monsoon pumpkin patch with Ruben’s squash

Many gardeners panicked in spring 2020 when the pandemic impacted supply chains and seed companies were overwhelmed and delayed. This is why I always grow some open-pollinated varieties, where pollination occurs by natural mechanisms such as insect, bird, wind, and humans. With pollen freely flowing between individuals, open-pollinated plants are also more genetically diverse. Each season, this variation within plant populations allows plants to adapt to local growing conditions and climate. The tulsi basil seeds from a Sedona gardener grow stronger and bloom earlier than any I can buy from the seed companies. When we let our gardens go to seed, the plants sow themselves, and decide when conditions are right to emerge in the spring.

Open pollinated Hopi black dye sunflower seeds drying

Last weekend our Rimrock library hosted a seed swap. In the room of about 10 people, there was a range of seed saving experience from novice to professional seed savers for market. A man who once owned a plant nursery is now intent on propagating wild milkweed from seed he collected locally. A newcomer brought bags of marigold seed to share, the only thing she could grow in her garden the first summer here. A basket maker who travels with handpruners in her car, shared seeds from a bouquet of garlic chives and wild grasses arranged in ceramic vase. The librarian had Mexican hat sunflowers she had collected from the side of the road in old prescription bottles. A man who just moved from Oregon, literally arrived with a truckload of winter squash and pumpkins he grew for seed, carefully isolating the varieties so we can enjoy eating the squash this year and for several to come.

Seed swap bounty

I brought Hopi black dye sunflower heads still drying in a big basket, as they have probably been grown around Montezuma Well for a very long time. Our seeds connect us to one another and our particular place, which is not an easy place to adapt and grow. In this way we tether ourselves to the fate of plants, we dance with the pollen flow, the bees, the wind and grow stronger together.

Family Gardens: The joys of growing together

By Kate Watters

The first day visiting my family in Vermont this summer began in my sister Kara’s garden. We sipped coffee and relieved our jet lag with a barefoot stroll through robust perennial islands displaying fireworks of color and texture. While we oohed and awed at the garden, Kara shared her ideas to revise and expand, yanking weeds as we walked. She inherited this established garden four years ago when they bought the house, and she and her family dug right in to make it their own.

Garden joy runs in my family—the love and work of growing, nurturing and eating plants.

I traveled with my Arizona sister, Kelly, who has been helping on my farm for the past two summers. This was our first visit home since COVID, and the changes were most apparent in Kara’s rapidly growing teenagers and our aging parents. In June, our mom fell on their soapstone hearth and fractured her lumbar spine. Much of our visit was spent problem solving and caregiving. In addition to washing her hair and helping her dress, my mom directed me to check the progress of the dahlias—tubers I gave her last year from my plants. I filled the house with bouquets from her perennials and the wild borders to bring the garden inside for her to enjoy. She suffers from neuropathy and it has been years since she has kneeled in the garden to pluck weeds and plant. She now observes daily progress from the screen porch.

At 83, my dad is still enthusiastic about tending his vegetable garden. The stone steps Kelly and I built on a visit ten years ago lead down to a grassy expanse edged with overgrown perennials and a wild bramble of raspberries and vines reclaiming the land that was stolen from them by lawn. Over the years his garden has shrunk to islands tucked along stone walls, in stock tanks and amongst a crumbling foundation of the shed I used to keep rabbits. I find myself itemizing the risks and treachery involved with every tomato he harvests—the tripping hazards, the awkward placement of gates and compost piles and hoses; weighing these against the joy he finds in a salad he grew from seed.

Planning the garden with my mom and dad photo by Kelly Watters

When I was a child, my dad tilled this ground each spring and the seeds we planted there took root in me and my sisters. Digging into this black soil again with a 100-year-old spade that conveyed with the 1877 stone house they bought nearly 50 years ago— reminds me that the mark of this place is imprinted on me. This vignette of weathered wooden fences, stone walls, red barn, framed by meadows full of wild flowers resonated a pleasing harmony in my heart.

The pleasing vignette of my dad’s garden

As I lived full summer days in the moist, green glory of Vermont, the reality of my other family still existed, far away in Arizona at 108 degrees. The farm, my flower babies, my honey and my dog; growing and living their routine. At first, I habitually checked the weather in Rimrock, but as I immersed in the urgency of our family homeland, thoughts of my own receded.

During 2020, my first year on the farm, I managed to be away for only three nights, due to COVID and the massive undertaking of establishing productive flower gardens. I felt like the mother of a newborn—bound by breastfeeding and fretting over everything. A year later, I have an automated irrigation system and realize that I am the one that needs to be weaned. Even with just over one acre, I marvel at the enormous, complex organism I am part of. So too is my family, and I wonder how it will be possible to care for both.

The last time I visited in summer of 2019, I was helping my dad recover from open heart surgery. He would send me to the garden to harvest something and I tried to imagine how in his frail condition he would be able to recover the strength to continue to garden safely. The health crisis he endured motivated him to alter his diet to whole foods and cut out sugar. He now spends his restored energy caring for my mom, but still has reserves to plant and plan next year’s garden (with raised beds right next to the house).

I marveled that the plant medicine we need is always nearby—the lush patches of stinging nettle, raspberry leaf, tulsi basil, the wild roadside weeds like chamomile and St. Johns wort. These plants help keep our immune systems strong, reduce inflammation and pain, and calm the nerves. Even the invasive Japanese knotweed we Kara’s family removed to access the brook can help treat Lyme disease, which has contributed to my mom’s neuropathy. “We grew up with so many good weeds!” Kelly exclaimed with delight.

Relaxing with Auntie Kelly on the mossy forest floor.

These woods, the places we have touched and known and grew us, I now see imprinted on Kara’s children. We visited their old homestead on West Street across from an apple orchard with a spring and woods and pastures and rock walls like the ones we had as children. Her kids grew up drinking from the spring, playing in the woods and pressing cider from the apples gleaned at the end of the season. The patio they built so carefully with hand-picked stones was engulfed by weeds. The blueberry bushes and peonies they planted almost 10 years ago were heavy with flowers and fruit despite no one there to tend or enjoy them. The forest path they maintained was overgrown with ferns and fir saplings. Fallen trees in various states of decay were disappearing into the silence of the forest floor to become rich soil. It's hard to even compare this version of lush to our riparian desert farm, which is green by Arizona standards but can hardly be considered in the same family. And yet it is somehow connected through us, like a root traveling underground seeking moisture.

We picked our way through these woods with her now teenage kids caught between the everyday wonder they experienced as children and the present escape of video games and social media. We rested on the soft carpets of verdant moss, and the sweetly uncurling ferns where the kids remembered building fairy houses. As we navigated the green thickness of tangled plant life climbing and clambering atop one another, they stopped to find sweetness in the tiny, delicious wild black raspberries hidden beneath it all. A reminder that wild garden delights are everywhere if we are paying attention.

Published in the AZ Daily Sun FlagLive.

Pollinator Gardens : Finding balance and beauty

by Kate Watters

June is National Pollinator Month and hopefully Flagstaff has made it through the last frost of the season so we can start to enjoy the benefit of pollinators in our gardens, both for joy and for higher vegetable yields. At Wild Heart Farm where I live and grow specialty cut flowers we are delighting in the daily drama of our pollinator garden.

Jeff Bowler and I stand together in the bones of the pollinator garden last August.

About a year ago, we received a grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Friends of the Verde River to create permanent pollinator habitat on our one-acre farm. There were days I regretted signing on to this ambitious project in my first year on this land and in the midst of a global pandemic. In order to transform the bare slope into a level terraces for plants to establish, we moved several tons of rocks and soil while temperatures hovered over 100 degrees. The high-maintenance dahlias I grow for wedding bouquets suffered with my divided attention, and I lost steam just at the time I needed to rally to plant thousands of fall bulbs. Yet today when I walk by the pollinator garden alive and in its prime, I do not regret any of it.

Hummingbirds are building their nests nearby and sipping nectar from the firecracker penstemon and salvia. The Palmer’s penstemon has curved and gangly stalks bearing giant, fragrant, pink flowers with wide open throats—a chorus singing songs of glory. The carpenter bees in particular are listening and smelling and responding. These native bees have formative stature, and gleaming black bodies. They clumsily hover around the flowers, squeezing themselves into a blossom while the entire stalk sways. I watched two sparring and tussling inside the same flower. These bees were not present last year. If you build it and plant it they will come!

Palmer’s penstemon from Plants for the People bloomed like crazy!

All shapes and sizes and species of bees visit the phaecilia flowers, a fast growing native with lavender flowers that unfurl like a scorpion tail. Our neighbor has honey bees and while I watch them happily forage in my cut flower garden on batchelor buttons and zinnias, I chose regional plants to attract native bees for the pollinator garden. Pollinators and plant diversity are inextricably linked. There are 20,000 bee species in the world, and 1700 reside in Arizona. Arizona is home to over 3500 plant species—the fourth highest plant diversity in the U.S.

On our microfarm bed space for cut flowers is at a premium, and I am often faced with difficult choices as I make my livelihood from the earth. Capitalism cries out “Grow more flowers! Make more money!” I feel the tension in my body as I step on the flower farming treadmill each morning crunching my crop plans, counting days to harvest, and finding markets for each bloom until every flower is grown, picked and sold. I could fill every square inch of the soil with a marketable crop and scale my farming operation to that level of production but it is not sustainable for the land or myself.

The pollinator garden is one way I take a stand against the extractive mindset, and grow something for a greater benefit, for the big picture, something that does not figure into my profit margin. This dance of business and farm owner is new to me and I am learning and adapting as if I am a mutualist partner with this land and these plants. Mutualisms are found everywhere in nature. Two species exchange goods or services and each receives a benefit from the interaction in an evolutionary agreement. That benefit usually comes at a cost, and both partners may not receive equal benefits or incur equal costs. Each species is operating on purely selfish motivations. The benefit is usually an unintended consequence of the interaction. This year we have a bumper crop of fruit in the orchard, thanks to the pollinators!

I watch the giant white moon blossoms of sacred datura flowers open each evening and enjoy their incredible fragrance. I also anticipate the giant tomato hornworms that will come to feast on its alkaloid-rich leaves before it transforms into a sphinx moth in its adult stage—one of the only species that can provide the service of pollination so this plant can make seeds. They are also dance partners throughout their life cycle, exchanging pollination services for protection as feeding on this plant makes the caterpillars toxic to predators. As I marvel at this mutualism, I often wonder as I go about my farm work what are the costs and benefits being exchanged between humans and the Earth? How can I balance this exchange?

Sacred datura blossom photo by Monica Mahoney

To sustain human life and plant diversity we need abundant pollinators, and yet pollinators are in decline. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture we are losing pollinator populations due to invasive pests and diseases, exposure to pesticides and other chemicals, loss of habitat, loss of species and genetic diversity, and a changing climate. Although it feels altruistic to plant a pollinator garden, it is truly an act of human survival, as over one third of the food we eat is thanks to pollinators.

I took a break from trellising sweet peas and sat on a rock in the pollinator garden. A Monarch butterfly flitted gracefully onto the scene. While once prevalent, today Monarch populations are in steep decline. I was surprised when this butterfly landed on a native cryptantha plant (literally Latin for hidden flower because they are so small) that volunteered in the cracks of the stone path. Beginning in March, these butterflies migrate from wintering grounds in Mexico and California and travel as far North as Canada. They need nectar to make the journey, and milkweed host plants to lay their eggs and provide food for their larvae so they can pupate and become adult butterflies (sometimes 2-3 generations during the summer) and the last adult returns to the wintering ground in the fall. I hope you will join me to celebrate National Pollinator Month by planting something in your backyard to attract pollinators and watch in wonder as the magic unfolds all around you.

Spring Awakening: A Desert Spring Baptism

by Kate Watters

I turned 50 years old this year on April 9. There was nothing I wanted more on this day than to wake up alone in the wilderness. It's not easy to extract oneself from a life caring for plants, especially as temperatures reach the 80s. Fortunately Beaver Creek Wilderness is just a few miles upstream of the farm. By late afternoon I had finished my chores and was on the trail with my faithful canine companion, Juju. Spring was in full swing, and my favorite plant allies were blooming along my journey—Indian paintbrush, sego lily and claret cup cactus. The reminder that wildflowers blossom abundantly without human tending filled me with joy. I am most alive and awake when I am in the wilds with plants. I never feel alone; I am cared for and welcomed in a deep way. Mary Oliver says it eloquently in the poem “Sleeping in the Forest.”

I thought the earth

remembered me, she

took me back so tenderly, arranging

her dark skirts, her pockets

full of lichens and seeds.

Desert creek baptism

The day was unusually hot for April, and when we reached the creek crossing about four miles in, I shed my clothes and sank into the cold creek water, watching the afternoon sun glow on the sandstone, the green tips of willows and ash trees dancing with their shadows. It felt like a baptism, to be born again with the spring energy, remembering what it is like to wake up, to be alive, and be glad to be here on this planet and in this life. I noticed the roots of a Gooding’s willow tree seamlessly growing around rocks to anchor into the shifting riverbed. I can’t imagine the strength it takes to live here. This being endures countless floods, testaments to time and flow, and yet always finds the earth—the source of life—even as it constantly changes.

Fifteen years ago I wrote an ode to a desert creek from this place and I am struck how the theme I explored then is still relevant to me.

There is something about a desert creek

on the eve of April

with spring dancing all through the air

traveling

on the wings of morning cloaks and swallowtails

flitting gracefully through the sky.

There is the newness of everything green,

just impossibly so, in technicolor shades.

Thousands of individual leaves greeting the world of the sun,

each in their own exuberance.

The sycamore leaf is soft and still curling inward,

twisting and lengthening into its greatest self,

unfurling

into a broad and merciful canopy;

that will offer the gift of deep shade in summer

then turn colors of umber and fall

to the ground in an earthen blanket.

I wish I could be like this leaf,

inventing myself again each spring,

coming alive

simple and green, new to this world,

awake to the wonder.

Living out long summer days in fullness

then releasing everything, letting go

and surrendering

floating easily to rest on the earth

becoming part of something greater

than me.

As I age, I sense my kinship growing with the plant world. They are old friends, teachers and elders. I take time to observe and listen to the wisdom they offer. I pay attention to the way they grow, rooted in place, adapting to the trials and extremes presented to them and still finding ways to bloom. As I grow and change I appreciate their resilience.

Claret cup cactus - offering clarity and collective abundance

Resting with a trailside claret cup cactus I feel alive, invigorated with overflowing creative life force energy. The claret cup is a cluster of columnar cacti clothed in spines. They huddle together like a crowd of protesters, or a clan holding ceremony. They press against one another as if garnering support and energy for whatever lies ahead. The red flowers are cups overflowing and glowing with abundance, as if lit from within. The chartreuse stigma, the sticky surface that guides pollen to the ovary tube, is like an exuberant jazz hand, luscious and alive, in perfect contrast to the red flower petals. This cacti colony seems to be at peace, looking out with the laser eye, full of strength and vitality from the collective. It takes a long time to build a community. At this stage in my life I feel like I am part of a growing cluster like this of people and plants rooted in place, offering our special gifts to the world.

Juju and I found a magical perch high above the creek framed by two tributaries with a view of the creek traveling downstream. As the sun set I listened to the wind swishing through the pinyon and juniper trees and heard the familiar music of canyon wren’s lilting evening song. It felt like a homecoming to find my roots in a familiar place—as if part of me has always lived here. Through the years I have taken refuge in this desert creek to experience the seasons, nurse heartaches, connect with the plants I love, with myself and the mystery beyond.

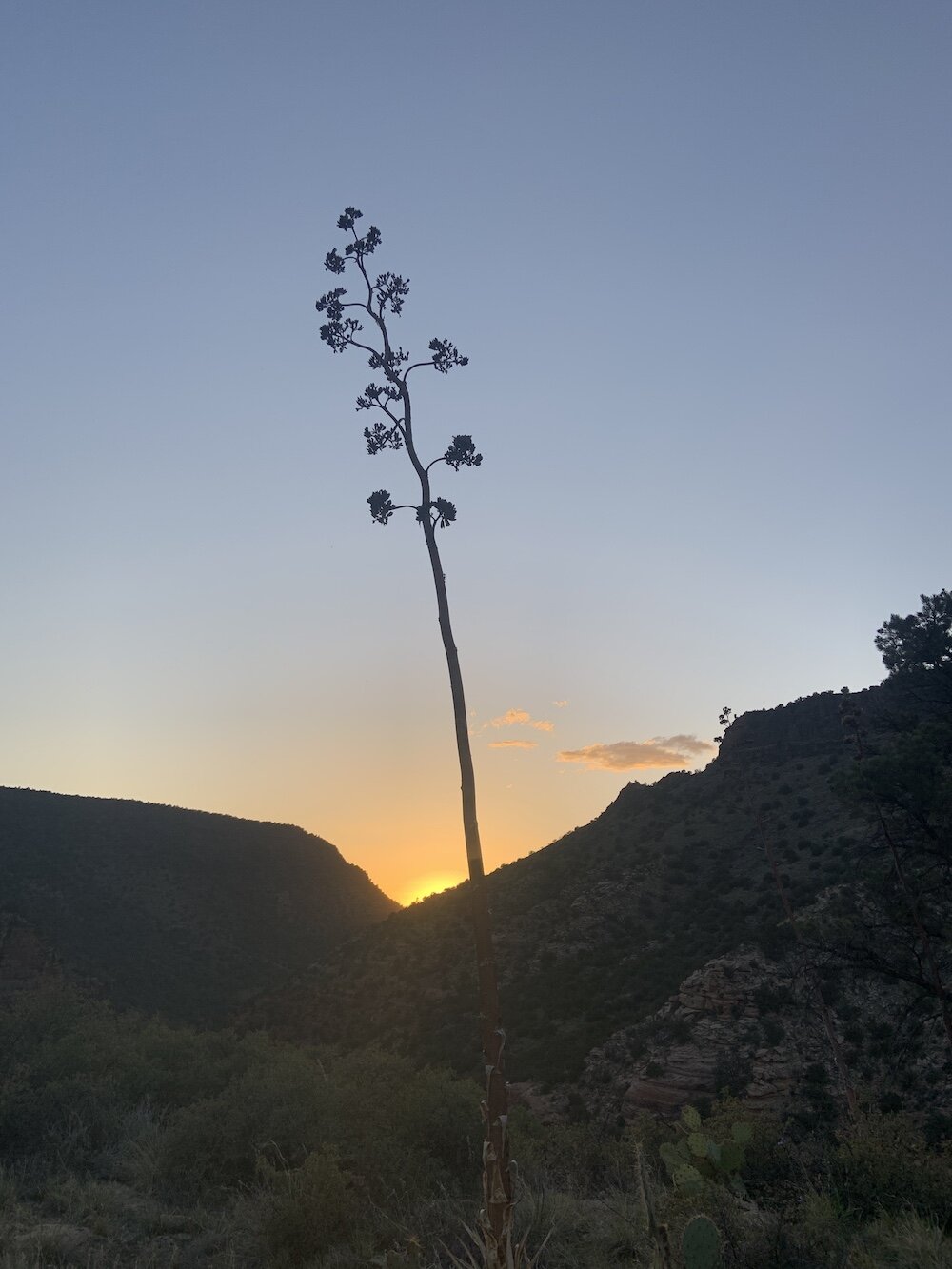

At my camp I watched the sun set behind the stately skeleton of an agave stalk. The curtains went down on the day and the stars emerged. Constellations came into view, growing brighter each moment. Agaves (also known as century plant) spend 25-100 years rooting in place before they shoot up a stalk, at which point the whole plant dies. To me they have always been sentinels bearing the message—this is your moment, give it all you got! Live the truth, to the solid core of who you are.

Agave skeleton at sunset

I meditated on the inevitability of my own death with the sculptural beauty of the agave in the darkness. Counting down from 10 years to 10 seconds left to live, waves of emotions swelled from grief to giddiness realizing each day is a gift and I only have time and energy for what is truly important.

I lay awake for a long time, staring at the vast night sky with Mary Oliver’s poem: “nothing between me and the white fire of the stars but my thoughts, and they floated light as moths among the branches to the perfect trees.”

Originally published in the FlagLive on April 22, 2021

Beginning Again

“It is spring again. The earth is like a child that knows poems by heart.

”

by Kate Watters

In early January I was planting the last of the daffodil bulbs, digging into the cold, not quite frozen earth, when my spade nearly sliced into a hibernating Woodhouse toad. I held the toad’s cold, stony body in my hands to try to detect a heartbeat. He looked vulnerable and yet peaceful. I immediately tucked him in to rest beneath the daffodils until spring. It has been quiet without the toads. Last summer they were a constant presence. They fed on the spiders, ants and insect larvae and hunted moths by our front stoop at night. In the heat of the day I would find them snoozing in the plant nursery, nestled with the succulents. I noticed the good work they were doing as I did my part to grow cut flowers and get them into people’s hands before they perished. Finding the hibernating toad reminded me that winter is a time to rest.

Apricot flowers in bloom, so early! The bees are mighty happy.

Tulips are poppin!

Our desert winter in Rimrock appears to be over and sooner than I would have liked. It felt like hitting the snooze button on your alarm, not like a long night’s sleep. The apricot trees are blooming, much to the delight of the bees, along with the pre-chilled tulips who were tricked into believing they had already experienced seven weeks of winter. The peonies are reaching their reddish fingers out of the ground and the robins are yanking worms from the new field. Just the other day I was preparing a garden bed and encountered a toad hunkered into the fluffy soil, wakeful and blinking. We are beginning again. It is time to climb out of our respective caves and replace our jammies with work clothes.

Spring is the official reset button on the farm season. Yet I’ve been wondering; what would it be like if we could begin again any time of year, from moment to moment? In a recent online retreat with Flagstaff Insight Meditation Community, I practiced beginning again with what brings ease and pleasure. For me, it was watching the chickadees and cedar waxwings try to share the birdbath. I slowed down and noticed the small wonders in my immediate grasp that can easily be overlooked as I blaze by on my way to the next task.

During a meditation, I find myself scheming, planning and generating ideas for Wild Heart Farm. It is my default setting to start dreaming up the plants I want to grow and what I will create with them. When I begin again, there is no remorse about these thoughts interfering with meditation. I simply note, planning, or dreaming, then go back to my breath.

As a farmer, you begin again every season. Mother Nature’s cycle is an unending circle of life. Everything dies, and you try to let go of your mistakes, the failures, the unmade progress, and start again. Last year at this time I was beginning for the first time on new land in Rimrock. I was in the midst of major life change turmoil—moving to a new place while still commuting to a beloved gardening job in Oak Creek Canyon. I was trying to summon the courage make the leap across the precipice to self-employed farm owner. I had no solid plan for how I was going to make a living selling flowers. Then the pandemic forced our economy into a screaming halt and canceled all the weddings I had scheduled. I had planned an entire season for the Oak Creek garden, and had to begin again from scratch in Rimrock. I had to buy all of my supplies, set up a greenhouse and get growing! To say I was frightened and overwhelmed is an understatement. I listened to flower podcasts for inspiration, and all I did was compare myself and feel worse.

I embraced the pandemic shutdown as a sign from the universe that I needed to root down and to learn how to grow in this place. Beginning again, I let go of the harsh, judging voice inside of me. I dropped the fear of failure I was carrying like extra baggage, and let go of my blooming garden in Oak Creek Canyon. The blank slate in farming is the bare bed; the soft, fluffy soil waiting to nurture new life. No weeds, no tangles of plants needing support, no aphid damage.

During the weekend meditation, I kept returning to the present moment for as long as I could before my mind carted me off to another land of make believe. I afforded myself a slower pace, and savored being awake as I completed tasks. I replaced the inner hustler with the encouraging voice of my meditation teacher, asking us to notice what happens when we invite ease. It turns out ease feels good! The dominant culture, and production flower growing does not allow for ease. It encourages us to move faster, plant more, take on more and it is rooted in fear and lack. I constantly compare my flowers to the pristine images on social media, and against the cheap, perfect roses at the grocery store. I now recognize this pattern arises from deep roots of the colonial mentality that our capitalist economy grows from.

Toads are coming out of hibernation and they are hungry!

This winter I went inside myself like the toad, dreaming beneath the daffodils. I softened a little, resolving to begin the season and each moment with ease and kindness toward myself. When I am overwhelmed by the mess of my potting shed, the unfilled irrigation trenches and the carpets of weeds germinating, I stop myself. I take a moment of gratitude that I am an earth tender, a partner in nature’s cycles. The imprint of last season’s lessons are planted in my body and the failures will bloom into new ways of seeing a problem. I will balance tasks that bring strife with those that invite ease. When I pass the delicate blossom of another anemone flower, so subtly unlike the last, I will stop and take it in its essence. I, too, can weather the harsh conditions of this world and grow the beauty that we need to nourish our souls.

Taking time to notice the exquisite beauty of the anemone flowers

The Portal: Reimagining our way through

Wintertime, with its lack of light, turns me inward. While my farm sleeps (its more like napping) I can reconnect with my writing practice. The first week of 2021 I retreated with my dearest friend, Karla, who I met while working on Grand Canyon trail crew in 1997. Since then, we have been seeking the truth of our lives through writing, wilderness and our vocations. For almost a decade, our annual retreat is a ritual to renew our friendship and our practice as writers. We write, read to one another, walk, drink wine and work through the obstacles (both real and perceived) to sharing our stories with larger audiences. We have both embraced a seasonal life cycle that grants us time away from the pressure and distractions of our day-to-day lives to write. Karla is a travel nurse who divides her year between hospitals in Montana and Arizona, at times living from a camper van.

This year, we stayed at Arcosanti, an urban planning project conceived by Paolo Soleri in 1970 as a response to rampant urban sprawl and consumerism. The place is an experiment in imagination and design where humans and environment interact in relation to one another. It was fitting to visit this living laboratory at a time in our current human history when we are in need of new ways of thinking and being. As we sought refuge from the outside world, reports reached us of a siege on the Capitol by a pro-Trump mob protesting the ratification of President-elect Joe Biden. In our rooftop Sky Suite with sweeping views, we stayed focused. The living room had a giant circular window that felt like the entrance to a portal. We gazed through it, transfixed, as if a new way of being in the world awaited us. The pandemic has ruptured the world as we know it, but there is no going back — we must reimagine our way forward. Karla and I have burned up the old habits that no longer serve us and are packing lightly for the journey to the other side.

Karla writing her way through the portal. Watch for her website: www.karlatheilen.com

Karla is a writer, live storyteller and NPR commentator who just finished a memoir about her six seasons on a wilderness fire lookout. Her current stories shed light on our broken health care system, and find humanity in the midst of the pandemic wreakage. During the retreat, Karla began a website for her writing, which in in itself is a portal; an invitation to her experience. I too have struggled to overcome this internal battle of feeling worthy of being found on the World Wide Web. Yet, I know that people are looking for her! Karla has traveled a great distance in her van, leaving behind her husband and dog, and family health struggles to take this time before she begins a COVID nursing assignment in Tucson.

I granted myself precious time away from farm responsibilities while the natural world is dormant. I sorted through writing files from the past 20 years to revisit, rethink and reorganize my work. I scrutinized each file and organized them by subject. To cross through this portal, I wanted to get clear. What stories might I offer? I had to rid myself of the unnecessary clutter; the old versions and the little scraps that have no place. Themes began emerging, like topographic lines on a map from above. I could see the carving and shaping of my self. The stories meander, like river ways flowing downstream guided from unseen forces. I sensed the fear and shame hidden in the earlier works, obscuring certain details to avoid discomfort. I wanted to make sense of things, but I navigated away from the difficult parts. Those details are still in the pages of my journals that I am working up the courage to share. Now I have a map to chart the route forward.

This process took the whole retreat, and I celebrated by singing my handful of original songs to test the acoustics throughout Arcosanti. It felt like a rite of passage, a moment of reflection before stepping through this portal into a new era; and to afford the time and space to be without judgement or internal pressure. A younger self would resist ease and try to produce something from an impossible standard of internal measure. Now I have faith because I realize — from what both Karla and have experienced — the creative process is a process. There are no rules and the timeline is expansive. Sometimes the creative bank account gets replenished by watching sunrises and sunsets, examining the dark, starry sky and listening to a friend weave stories.

Kate singing her way through the portal into a new era of creative being in the world

Situated on the rim of a rugged canyon, the sun-baked concrete of Arcosanti radiated with a strangely earthly essence. I appreciated the human design conscious with nature, a filing images in my mind for creating space on the farm. The succulents arranged in borders along paths; the Mind Trail meandering through olive trees to the canyon edge; the colors and textures in the concrete impressed from river, sand and stone. You could sense the living, breathing and creating by other past and present beings all around you.

We watched the light travel throughout the day; playing off walls and streaming through windows. The portal framed the waning moon and constellations. The elements of metal, wood and concrete against earth and sky was pleasing and grounding — a perfect balance of alchemy. Our food was simple and nourishing; the sleep was deep and satisfying; the company comforting and uplifting. With much earthly work ahead for both of us, we created the necessary energy reserves and momentum.

Karla’s friendship is a home; a familiar place I can keep returning to, and like a maple tree growing in the yard, I can measure my own growth against its spreading canopy. I am lucky to have a friend to share the creative journey. If one of us is winning, we both win. We can celebrate when one of us breaks through and shines the light on something no one else could see.

Light plays off the organic shapes and colors made with earthen materials

The creative work of so many beings past and present at Arcosanti

Small details everywhere to blend natural and human realms

A Handmade Life: Creativity and Healing

Last week I called my mom to wish her a happy birthday. In many ways her life is a miracle. The day she was born her mother, Lorena, died in childbirth. They were only able to save her. “I thought about my mother all day,” she tells me over the phone. When I hang up, a wave of grief flows out of me in great sobs. I still feel the loss of Lorena, not just for my mom, but for myself; for the grandmother I never knew.

Over the course of my life my mother has recounted the events of her birth without emotion, as if a distant narrator. I remember when she showed me the scar on her right arm; a mark from when the doctors cut her yet-to-be newborn skin as they struggled to remove her from her dying mother. I felt sad when I heard the details of the story, and noticed the tough, protective layer my mother formed to shield herself from the devastation. I have tried to imagine wrestling with a loss that is inextricably linked to the wonder of your own life. “My mother made the ultimate sacrifice,” my mom explained to me once. In my mother’s story, motherhood is a sacrifice of love. I believe there is another story of creativity and healing unfolding.

The details of Lorena’s life remained a mystery to my mom, lost in her father’s desperation to find another wife to raise this child. He buried the memories of the woman he loved alongside his grief deep inside his heart. Over the years it grew into guilt, anger and regret. He was a hard-working, stoic man who rarely expressed affection and had a quick temper. Lorena’s death was hidden from my mother until she was a teenager. The truth was cruelly exposed to her on the playground from teasing classmates.

Subterranean pain is like a weed in my garden with a spreading root system connected to a mother plant. It grows ghostly and white underground, feeding on resources and eventually finding its way to the surface on the other side of the garden where it tangles with the roots of the other flowers trying to bloom. I hold the ache of these stories inside me. They are released when I create something from my heart, which is what I learned from my mom.

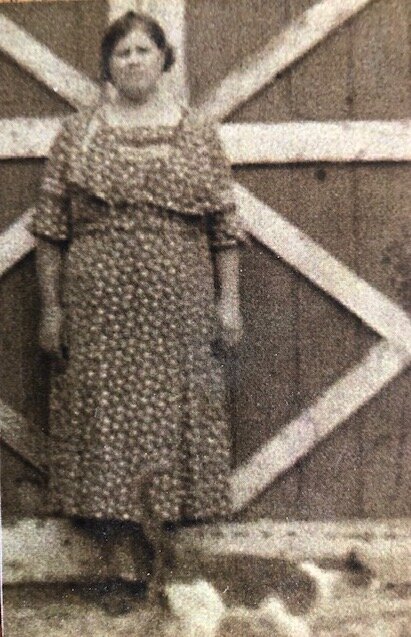

The only photo of Lorena I have is of a blurred, heavy-set woman in a long, calico dress standing in front of a barn door; a cat at her feet. I can’t tell if she is squinting or smiling, or if she is wearing a house dress or a Sunday dress. What is the occasion? Who was she in this moment?

The only photo I have of my grandmother, Lorena

I am getting to know Lorena, at least in spirit. On the farm this summer, the great grandmother cottonwood and ash trees whispered to me and I felt comfort in their strong roots and trunks and exuberant, towering branches. I found refuge in climbing trees when I was little, so perhaps even then I was seeking my grandmother’s wisdom.

I can now imagine what Lorena’s days were like when she was carrying my mom inside her. She was singing, planting, baking and making. My mom received those messages of love. Lorena’s love of making has been infused into the line of women that she originated, and it is now hardwired into the souls of my mother, myself, and my two sisters. I feel her spirit this week I weave what I have grown and gathered into wreaths for people to enjoy.

My mom has always expressed this love of creating and sharing the gifts she makes. She was also baking and stitching and dreaming when I was a seed growing inside her. She became an entrepreneur, and her handmade doll business, Bonnie’s Bundles Dolls, has been her passion for 50 years! I believe it was creativity that saved my mom’s life. She can keep giving birth to something new again and again. With every doll creation, she brings another soul joy.

My mom, Bonnie, at an art fair selling her creations from Bonnie’s Bundles Dolls

Photo by Lew Watters

During our summer vacations she required that we played outside and kept a journal to write stories and draw. God forbid we would enter the house, where she was creating dolls, and claim we were bored. She would quip, “IF YOU'RE BORED, YOU'RE BORING!” She taught our girl scout troop how to bake a pineapple upside down cake in a reflector oven while camping, and how to make miniskirts without a pattern. Growing up, we spent our summer weekends at craft fairs where she would sell her handmade dolls from an elaborate booth. She encouraged me to follow my business ideas, so while other kids were selling lemonade, my business plan was miniskirts and hand-lettered birthday banners.

Here I am selling my plant-inspired creations at the farmer’s market

I still struggle to own my creativity. At first I made art to make my mom happy, for her to love me and see me, and for her to feel good about herself. Now I make art to understand my own journey in the world and heal the wounds. As I write this, the realization is tangled in the emotions from the women in my line. When it comes out I feel a sense of relief.

As I get older I feel a softening around my mom. She is always creating something new, whether it’s a batch of brownies, a doll or a poem. As I age, I feel less judgment and more awe at what she had to overcome. Her creation process is a form of survival. I’m grateful for her example of a handmade life. I know this is something only I can create, with my soul and through all of my ancestors who left their recipes and songs and patterns on my DNA for me to express in my lifetime.

Published in the FlagLive December 17, 2020

Letting it Go: A lesson from rosemary

I rang the bell in the October dawn light to open our first silent mediation retreat at Wild Heart Farm, our one-acre farmstead in Rimrock where my partner Mike and I have lived since early this year. When Mike and my friend Molly first proposed the three of us do a self-directed silent farm meditation retreat, I felt resistance. The idea of doing nothing but alternating between walking and sitting meditation for the weekend felt like a luxury I could not afford. A long list of end-of-season farm tasks loomed. I feared I would not be able let go of the work I thought I needed to do and that my distraction would ruin the experience for others. But after an entire summer of nonstop doing on the farm I decided I needed a reset.

The farm itself has been a long time dream and central to my meditation journey. It began a year ago when we first saw this place and fell in love, and in the same moment, learned the sellers had accepted another offer. We waited patiently in second place, and as the other buyers moved forward with the purchase we put in a counteroffer with a heartfelt letter and tried to let it go. Six weeks later, and just days before Mike and I began our first 10-day silent Vipassana meditation retreat in Joshua Tree, the sellers accepted our offer. We scrambled to sign paperwork and get things in order before the retreat where we would surrender our phones, and follow strict guidelines to have no contact with the outside world. Even Mike and I would be completely separated. Though I was full of doubt right up to the hours before whether I should still go ahead with the retreat, something told me that this was exactly what I needed.

On day two of the retreat I was not able to sit for more than 20 minutes without pain requiring me to shift my position mid-meditation. While I was supposed to be focused only on breath, my mind raced with constant thoughts about the farm—from what I would grow to the logistics of moving and how I would keep my full-time gardening job while caring for my own farm.

That morning, I noticed the gardener trimming the rosemary bush near my room. It was a massive, sprawling plant speckled with shining, purple-blue flowers, blooming in the midst of the darkest winter days. I immediately desired the discarded plant material to freshen up my room. Scented products were prohibited at the retreat, which was a form of torture to me. Aromas, especially the essential oils of plants, ground and uplift me. I could barely sleep without the Chill Pill aromatherapy blend on my pillow.

I took pleasure in stroking the deep green leaves and inhaling the pungent aroma on my way back and forth to the meditation hall. Rosemary essential oil helps improve moods, boost mental activity and concentration. Walking by after the morning session, I noticed a branch with roots laying on the ground and immediately thought of taking this sacred rosemary to plant at my new farm sanctuary. It would be a reminder of this retreat, and a story I could tell. I snuck it into my room, wrapped the roots in a moist hankie, and hid it in a trash bag. Immediately, I worried I might be violating one of the Buddhist precepts I had vowed to follow by taking something that was not freely given. But what if this discarded plant scrap was freely given by the plant itself, or maybe even given subconsciously by the gardener?

The rosemary plants growing at the Southern California Vipassana Center grounded and centered me.

My mind did the mental gymnastics as I walked the path on breaks and shifted on my thin meditation cushions. I decided to ask the teachers about it during the interview period after lunch as I had signed up for sitting instruction pointers. I was afraid I would never be able to sit still for one whole hour, let alone the 10 required of us each day.

The interview room was full of windows and bare bone winter light. Both teachers wore white shawls and sat serenely crosslegged with eyes closed as I entered. I asked what I should do about sitting as nothing was working. One teacher advised matter of factly, “Keep working on it.” Since I still had time left in my five-minute slot I presented my quandary about the rosemary.

“It sounds like it is very distracting for you, my advice would be to let it go.” I was shocked by the simplicity of her answer.

I went outside into the desert rain, steady and soaking. I opened the big, black umbrella on loan from the center and took this new concept of letting it go to the walking path. A great swell of grief and relief buoyed me along as my tears mingled with the winter rain. I began to let go of the need to save every plant, to grasp after things that only filled space, and claimed my attention and my precious time.

While meditating last weekend at the farm, I was not free of thought or pain. Distracting thoughts arose—constant planning, worry about my finances and the flowers as frost loomed, and sadness and clinging to their aliveness. Each time I returned to my breath and my body to anchor me in the present moment. I let the constant barrage of thoughts go, one by one. I felt lighter, at ease, grounded in this place of innate beauty that needs nothing but my loving attention. After all, where we place our attention is what grows. I can see that my plants have grown from my care, but what else needs attending to? What remains when I let go?

When the bell rang out signaling the end of the last meditation I noticed the pungent scent of the established rosemary plant that was here when we moved to the farm growing happily, and remembered the one I had left behind at the retreat center. The plant at the retreat center had been a great ally and teacher on the practice of letting go and staying present. Now this one on the farm offers a daily dose of mindfulness to keep noticing what is already here in the present moment.

Wild Heart Farm rosemary growing by the bell next to the flower garden now lost to frost. Photo by the author

Blazing the trail for women: a tribute to ruth bader ginsburg

In the wake of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death this week I have been experiencing many emotions. The first is anger, seminal and cleansing. I am angry at the patriarchal system that we have still not been able to dismantle. Angry thinking about all the times Ginsburg sat alone in a room full of men and had to work twice as hard to be heard. Angry for all the times she was discounted and questioned. Angry at myself for all the times in my life I questioned myself and did not speak up. Angry at assumptions that are made about women. That it is assumed I have a husband who does the tractor work and irrigation on this farm, when, I-beg-your-pardon, I do it. Angry that instead of having the option of hiring women, I had to hire men to excavate, haul soil, move rocks, build fences and design irrigation. As the fire of anger burned out I was swept away into a river of tears mourning the loss of Ginsburg, the fierce, intelligent soul who fought for justice and equality and changed the world for all people through her actions.

Back in January of 2020 when the year was new and full of possibility, I cloistered myself in a trailer in Patagonia, Arizona, for a few days of writing and visioning. In a matter of weeks, I would become the owner of a one-acre farm in the Verde Valley. I would leave my full-time gardener job to earn a fully self-employed living from this land growing flowers. There was work ahead and I wanted to map it out.

One evening around sunset I drove out Harshaw Creek Road, craving a stretch of dirt to run down with no particular destination in mind. I came to the Red Mountain Trailhead. It all seemed so familiar, the curves in the road, the mountains etched with rock outcroppings glowing in the evening fade. I realized that here, 26 years ago, is where I began my journey into leadership. I was a new college graduate, fresh off the train from the East Coast, and crew boss of a dozen 18-25-year-olds. We would spend a year living and working together to build and connect the Arizona Trail.

As I ran up the trail in the waning winter light I briefly thought of lurking mountain lions. Still, I set prudence aside. I had to put my feet to this path, the place where so many things began: my love affairs with my first husband and the wilderness, and the place where I came into my shovel-to-earth physical strength. This is also where I solidified the idea that the most unlikely group of people could become family through a bond created out of good, hard work in nature. As I ran by a patch of alkali sacaton grass, the pale yellow seed stalks taller than me, I marveled at the bravery of my young self, stepping so fiercely and unquestioningly into the role of crew leader.

I had no previous experience, save being the eldest sister. That role came with its own innate leadership skills. Elder sisterhood required living your own hard knocks first and then desperately acting to shield the ones after you from making mistakes, from getting their hearts broken, from taking the wrong turns and getting lost. I had big sister trail blazer abilities. I have been breaking new trail in my family all my life and telling my younger sisters what to do ever since I could talk.

I gave a nod to my younger self who was battling fear and naysayer voices that today I still hear blasting from my inner loudspeaker: You have no experience. You are going to fall flat on your face. No one will respect you because you are a woman. You have no authority over this subject. No one is going to listen to what you have to say.

In that moment, I felt such tenderness toward that fearless young woman who stepped into leadership without talking herself out of it. Without her I would not be running along this trail at dusk enjoying this freedom in nature. A flutter of small birds startled from the grasses, probably feeding on a meal of seeds and insects residing there. My heart jumped in reaction. The sound of wings and bird words broke the silence and brought me back from the distant past to my body in this moment. I felt my breath and my steady heartbeat pounding. A bubble of gratitude rose in my throat, to have believed enough in myself to have taken those leaps of faith. That same young woman is inside of me to navigate the trail ahead, as loving partner, big sister, farm owner, business woman and community leader.

This weekend a group of my plant lady boss friends gathered on our farm to plant our pollinator garden terraces. One will be the RBG Memorial Garden built in the heat of the monsoon-less desert summer by me, orchestrating a group of men to carry out a collective vision. We circled up; each woman shared what she intended to plant in this place and in the world in Ginsburg’s honor. Fraught by how divided and hopeless we felt, words like compassion, deep listening, fierce love and hope mingled with our shovels in the soil, and with the roots of ocotillo, sacred datura and milkweed plants. We took to the work with words spoken by Ginsburg: “Fight for the things you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.” I will be fighting with love.

The Ruth Bader Ginsburg memorial pollinator garden

A Sister Witness: First Summer on the Farm

One unexpected delight of the Coronavirus has been the presence my sister Kelly on our farm this summer. She was en route to Vermont to visit the rest of our family, as her work in the school system allows for seasonal migrations. The painful reality of a worsening global pandemic dashed her plans and she decided to shelter in place with us. In the short weeks she had been at the farm, Kelly had already started to grow roots. The seeds she planted had emerged and were rapidly growing into toddlers.

Kelly and our plant babies for the Flower Garden CSA (Community Supported Agriculture)

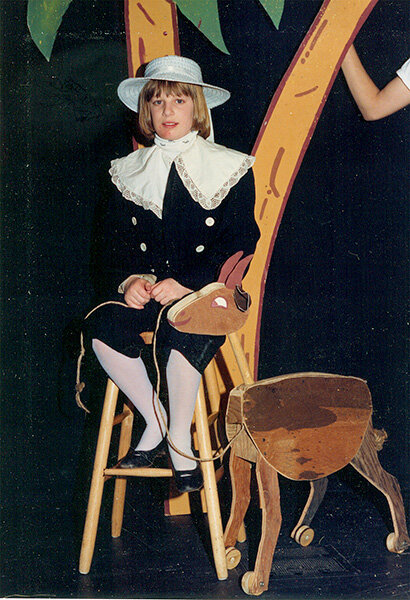

Kelly is the youngest sister of three so she has witnessed many aspects of evolving family life through the years. She was dragged to drama rehearsals and played all of our walk-on kid roles—she knew our lines better than we did. She watched our primping rituals for high school dances interjecting commentary about the people we thought we needed to be as we curled our hair and applied makeup. She schlepped our belongings up flights of stairs to our college dorms—helping us hang tapestries and shelve our new books. She settled us into these new, exciting lives with resignation, keen observation and wry humor.

Kelly playing a walk-on shepherd in our high school production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

Our lives seem longer and more brightly-colored when witnessed through the eyes of another, especially someone who has known you your whole life. The stories sisters tell about each other have more grandeur, elicit bigger laughs and usually lack filters. The chapters get right to the point and are brutally honest, especially when critiquing relationship eras. As sisters, there are times we have to painfully watch a bad scene play out, while compassionately waiting in the wings wanting to call curtain. There are also times where swift, direct action has been applied to a situation without commentary or questioning. We have shown up for each other during times of crisis, break ups and break downs, to console was seems inconsolable often with gardening, cooking and music.

Sister retreat on the Brandi Carlile Pindrop Tour

There is a deep comfort to a sister’s love and companionship. You are bound by family origin and there is a safety net that you weave together out of silken moments you share from your very first memories. It is strong and magical like a spider’s web but most of the time you don’t know its even there. Then one day something earth shattering happens and you feel the invisible threads holding you, suspended.

When I first moved to the farm early this year I was amazed by how familiar the land felt under my feet, like true home. I was returning to my child self who lived beneath big trees and played in the dirt, had wild places to walk dirt roads and creeks to swim in. This is where Kelly found me in June and she dug in right alongside me. She picked up the weed wacker without a second thought and started putting things in order, helping me unpack boxes, organize my spice drawer, and build my farm nest.

Kelly and me laying down a lot of chicken manure and cardboard for a new garden area

Kelly was here this summer to see me unravel under the weight of caring for plants, soil and all the beings who dwell here, as my bank account shrank and I hustled flowers to fill it back up. She also was by my side when, at 10 years old, I started digging a pond in our backyard for goldfish and frogs, and I think she believed I could do it then (even though now you can only see a slight divot in the earth at my efforts.)

We were together when the wounds of early childhood were created, the unconscious patterns etched in us from our parents, and their parents going back to unknown generations of trauma, loss and overcoming. Grounded on the farm under the canopies of giant ash, ancient pear and hackberry trees we began to let go of these old stories. Like the cicadas, who cracked open their exoskeletons, we shed the deeply held beliefs ingrained in us about who we should be. We sorted it out together as we untangled seasons of Bermuda grass roots that had taken over the flower beds, mixed soil for seedlings, made bouquets and scones for the farm CSA members (community supported agriculture). We planted new seeds together to nourish ourselves, and developed new patterns of self care by picking herbs for sweet baths, yoga sessions and swimming in the creek. We watched the moon begin as a sliver and grow full three times, each cycle manifesting more of our desires. We spoke them to the trees, and left notes in the dark holes inside the oldest of them for the fairies to bless.

Kelly and me awkwardly navigating the teenage years.

This will be Kelly’s last week with me on the farm. Each day has been an act of faith. This is how planting seeds and following a dream feels. I am still awed by how enormous and green and tangled the plants grow. But dreams, like seeds, do grow, with our care and attention. The sunflowers we planted look like a crowd gathering with fists raised, triumphant. This is how I feel with my sister by my side again.

When the long, hot, full summer days reach an end we sit outside and watch them dissolve, feeling the ache of work inside our bodies. The toads hop around us, and Juju, the dog, sits at our feet. The spiders weave their webs, encircling us in the beautiful, complicated and sometimes heartbreaking cycle of nature we find ourselves intertwined with. We watch the big dipper grow brighter in the sky between the forked ash tree branches, holding all the moments from the day—the sweat, the joy, the tears, the challenges, the sweetness and the magic. The sparkling effervescence of our shared experience in this time and place spills over us in the now starry darkness.

Sister Kelly literally became entwined with the farm. Flower designs by Agave Maria Botanicals and The Happy Vine

Week One Flower Bouquet CSA: The bride of amazement

This is your first week in flowers. When I gathered all the buckets together and saw the silver-white, blush and lavender I felt like I was heading to a wedding! So the title of this bouquet is The Bride of Amazement. It is inspired by a line from a Mary Oliver poem When Death Comes.

“When it’s over, I want to say: all my life I was a bride married to amazement. I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.”

I often hear people lamenting that they wish they could get married so they can have a "reason" for me to create beautiful floral designs for them. While I delight in making amazing wedding flower arrangements, I resent our culture that obliges marriage as the ultimate moment for a woman to celebrate herself. I believe that flower rituals should be sown into so many more of our life moments. Let today’s bouquet be a moment for you to celebrate loving yourself, being married not to another being, but to the amazement you find in the world.

Joan, a CSA member is an artist and bride of amazement

Jason, a creative and loyal bouquet customer is wedded to amazement

The elements in this week's design include:

Blush and apricot lisianthus: this luscious beauty is in the gentian family and the genus Eustoma grows in prairies in the warmer parts of the world. These seeds were sown in January, by a commercial grower in VT who I sometimes buy the harder-to-grow flowers from in plug trays of hundreds of plants. I planted them the first week of April and they are in full shine now.

The beauty of lisianthus makes me giddy with delight! This flower shall not be reserved only for wedding days

Queen Anne's Lace: This delicate, lacy flower is found in meadows and is in the carrot family. The wide landing zone of tiny flowers making up the bloom attracts many beneficial insects. If you find ladybugs, just take them outside!

Butterfly bush: I love the deep purple spikes and honey-like fragrance that emanates from this hardy bush. As its name suggests it attracts butterflies and pollinators of all kinds.

Bluebeard: Another hardy perennial shrub that thrives in full sun. I love the fragrant, silvery foliage that gives it away to being a mint family relative.

Russian olive: I used to kill these trees, now I love them! These trees are highly exotic in our desert waterways, so I feel really good about randomly harvesting some branches from around Flagstaff. Birds love the olives and are somewhat responsible for their spread, combined with land management practices that dam rivers and put our natives at a disadvantage.

Hand-tied bouquets ready to be delivered to our CSA members.

The Intricate Web: Farms and people need one another

The creeping tendrils of the COVID-19 virus has touched every aspect of life all around the world. The virus reminds us each day that we are an interconnected web of humanity and nature woven into a thick cloth. To realize this is a beautiful gift despite all the losses hardships it has brought with it.

With mother nature as my business partner, I am tangled in a vast web on my farm and my goal as a natural farmer is not to disturb or destroy it. On my daily rounds in the high tunnel greenhouse, a covered growing space with no heat or cooling, I noticed aphids have taken residence on the leaves of oats (Avena sativa). I am growing this grass as a cover crop to replenish the soil and feed the microorganisms underground to grow heathy plants. Another benefit of the oats is their milky seeds can be made into a powerful nervous system restorative (something we could all use right now!) Each day I check for the flowering stalks to emerge. First discouraged by the presence of the apids, who suck energy from the plants, I felt relief when I noticed the ladybugs (technically ladybeetles) perched on the blades of grass feasting on the aphids. What a great forest of food this is to them! My problem has been solved, or at least lessened. No need to pull out the neem oil to knock back the aphids. The web is at work!

Five years ago I began my journey to become a farmer at University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. I left my lucrative job, sold my house and put everything I owned in storage. I packed my Subaru with a few essential belongings, including my guitar, cowboy boots, typewriter and my camping gear and headed West. At the UCSC farm the apprentices slept in yurts flanked by a field of vegetables and an orchard and perched at the edge of a coastal redwood forest. At night I drifted off to sleep while the barn owls shrieked and coyotes howled. In the morning I walked out to the fields to work and learn in rows of vegetables which seemed to grow into the Pacific Ocean. Some harvest mornings we could hear sea lions barking as we bunched rainbow chard and filled wheelbarrows full of beets. The web of life was thick there, and I began to see how as a farmer I was essentially creating an ecosystem each year from bare ground, and I needed all the help I could get from various organisms to keep it healthy and in balance.

Rows of vegetables at University of Santa Cruz Farm and Garden

At the UCSC farm I immediately felt at home and steeped in daily wonder, much like I had years before exploring the natural world in the Grand Canyon. Yet the earthly abundance and diversity I experienced in my Santa Cruz farm life was in apples, blueberries, dahlia flowers and heirloom rose varieties. This fed me on a deep level to be fostering these wonders from the ground, sharing them with our fellow apprentices, and offering them to people at our market stand. But there was another element woven into the complex cloth of this farm ecosystem—the other farm apprentices. Together forty would-be farmers from vastly different ages, cultures, orientations and life experiences grew together out of that beautiful soil fertilized by nearly fifty years of apprentices who came before us.

The 2015 Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems apprentice crew

Today I am settling into my first full days at Wild Heart Farm, on my new land in Rimrock, where I am dreaming, building, planting, and creating something from all the seeds I planted, cuttings I propagated, and trees I pruned at the UCSC farm. The varieties of flowers I love, the ideas, techniques, the soil preparation and reverence I feel and songs I sing were planted in me from that experience on the UCSC farm and my wild, native plant friends from the Grand Canyon. The missing piece on my farm during COVID-19 has been people, since we have all been isolated and sheltering in our place.